First Sunday after Christmas, Feast of the Holy Family, Year B

Readings – English / Español

(I chose Genesis and Hebrews, the Year B options.)

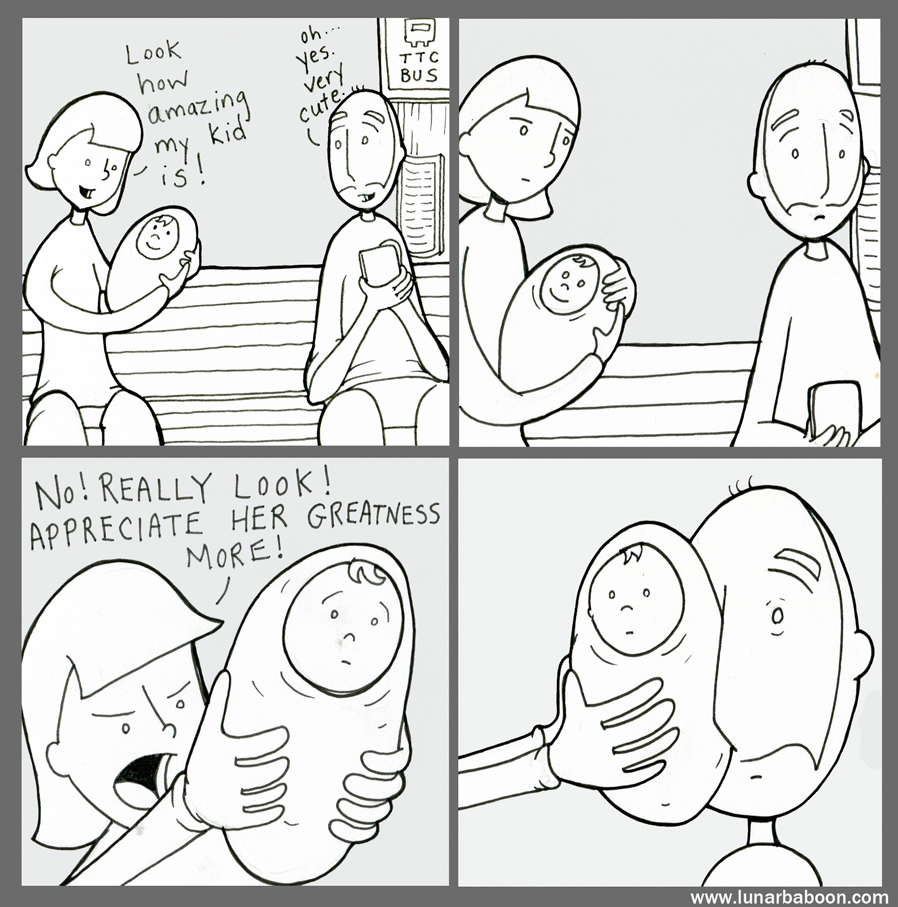

Featured image found here.

English

My relationship with my father, like the relationship between all fathers and sons, is complicated. My dad likes anything with an engine, and is happiest when he is washing or maintaining or fixing up his variety of cars, trucks, boats, and motorbikes. He would always have me out helping him, of course, but I found it all very boring. I much preferred to be inside, playing with my Legos or my Erector set, or reading a book. At some point, I realized that our divergent interests were a source of sadness for my dad. I am his first child and only son, and he wanted to share with me all of the things that he loved, but I was just not interested. And, visa-versa, it has been hard for my rarely-attending Presbyterian father to get excited about the religious passions of his son the Catholic priest.

I am telling you this because thinking about my own dad helps me to understand Abram in our first reading, and why Abram was so insistent on having an heir that was his own child. I believe it was because Abram, like my own father, like any father, wanted to know that there was someone coming after him who was like him.

I do not know why this is such a strong human desire, but it is. Some have suggested that we seek heirs because we seek immortality through them, so the more like us they are, the more immortal we feel. Personally, I think it is because likeness breeds trust. The more like us someone is, the more we trust them. So if we are going to hand over our life’s work, we want to give it to someone who is like us, because we trust that they will carry it forward properly. We trust that we are giving it to our younger selves, and not some stranger. Let’s call this impulse the “mini-me complex.”

Now, as natural as the mini-me complex is, as much as it cuts across eras and cultures, the point of this homily is not to commend it, but to attack it, for two reasons. The first is because it distracts us from what is truly important, and the second is because it makes us feel undeservedly guilty about our children.

So, to the first: which is more important, the action or the result? Most of us have been trained to answer “the result” because if something does not have an effect that lasts, it seems futile and meaningless. But this is antithetical to Catholic thinking. We Christians know that God only holds us accountable for those things we can control, which is to say, our actions. We cannot control whether our actions bring the desired results or not, so God does not pay any attention to the results. The problem, then, with the mini-me complex, with the obsession about an heir, is that it puts our focus and our hope on something that we cannot control and that God does not care about. My friends, we are not judged by our legacy. Rather than asking “what will happen when I am gone” we should be asking “Am I striving to be the best person I can be? Am I determined to do the best work I can with the time and resources that I have?” And if we can answer “yes” to these questions, if we can honestly say that we are doing our best, then nothing else matters, not even the future.

The second reason to abandon the mini-me complex is because I have seen far too many people feel guilty about their children. To use another example from my own relationship with my dad: I decided to go to an experimental, unknown college, which my dad thought was a horrible idea when I also had offer letters from Columbia and Rice and the UW Honors Program. And then a few years later, when he had finally made peace with that decision, I told him I was throwing it all away anyway to become a Catholic priest. In both cases my dad thought these were radical, unwise decisions, and in both cases he felt like he could have or should have done more to influence me before I made these choices. Yes, maybe had the divorce not happened, maybe had we lived in the same state, things could have been different. Or maybe I am stubborn, argumentative, and self-assured, and I was going to make my own crazy decisions anyway. Pro-tip: it was probably option number two.

The problem with the mini-me complex is that it convinces us that we somehow do or should have control over our children, and so if our kids do not turn out exactly like we expect (which is usually to say, an improved version of everything we like about ourselves), then we think we have somehow failed.

Well, we need to stop it!

We all need to admit to ourselves that children have free will, same as us. I cannot tell you how many people come into Confession and confess the sins of their children. STOP. IT. When a person older than the age of seven makes a choice, they and they alone will be held responsible for it. There is a reason that we do not allow parents to accompany even their third graders into the Confessional. Yes, children certainly need the guidance of their parents, from the age of seven all the way to the age of fifty-seven, but the burden of freedom rests equally on us all, and no one, not even someone as influential as a parent, can take responsibility for the free choices of another.

This, I believe, is ultimately why God asked Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, which is discussed in our second reading today. Abraham in our first reading was so focused on procuring an heir from his own bloodline that he fell head-first into the mini-me complex. So to show Abraham how little control he actually had over his future, God asked Abraham to give Isaac up; and, to Abraham’s eternal credit, he trusts God and does it. In so doing (now pay attention, this is the important part), in so doing, Abraham received Isaac back. In other words, by giving up control over Isaac, Abraham receives back his son in a new and better way, as a gift rather than a tool of immortality.

I firmly believe that this is what God desires for parents, that they should always receive their children as a gift. Even when these apples have fallen very, very far from the tree. Even when these kids are doing stupid stuff, causing family drama, or are otherwise being stubborn, argumentative, and self-assured. Even then they are a gift. But this requires giving up control and, at a certain point, even responsibility for these children. Because a gift always comes from the outside. If we continue to think that our children are merely an extension of ourselves, that they must be exactly like their parents, then they can never be a gift, because we can never think of them as outside of us. But if we can see children as independent, unique, individuals, given to us for a time by God, but never completely ours, then we will receive them back as the gift that they are.

This is not to say that parents should have a hands-off attitude. Far from it! Parents have a grave responsibility to form their children with a Christian worldview and Christian habits. But, again, this formation cannot be judged by the results, but only by each moment in time, because these moments are the only things we can control.

This is also not to say that every divergent decision is irrelevant and meaningless. My dad provided an important viewpoint and was right to be critical about decisions that had profound effects on my future. Many of our children choose to walk away from a sacramental relationship with Jesus, and we are right to try to call them back to the Lord. But the fact remains that children have free will. The burden of freedom rests equally on us all. After the age of eighteen, a poor, stupid, or unwise decision is best addressed with love, mercy, and compassion, rather than guilt, anger, or shame.

Finally, probably because they are the Holy Family, Mary and Joseph give us an excellent example in today’s Gospel of not falling prey to the temptation to control. If I were them at the Temple, I would be freaking out. Some guy grabs the baby and yells “I can finally die. I have seen the glory of Israel!” And then this old lady comes up to them and starts to preach to the entire temple about how awesome this baby is. Other than going to hide under a rock, what were Mary and Joseph supposed to do about all this? Their kid is attracting a bunch of crazies, and there doesn’t seem to be anything they can do to stop it.

What is beautiful about the example of these holy parents is that they do not do anything. They do not try to stop what is happening, because they know they have absolutely no control over the situation, and that their son will do many things, and have many things done to him, that they do not understand. So they focus on what they can control. They dutifully perform the temple sacrifices like they came to do, and then they go home and raise their son as best as they can. Jesus is going to be Jesus, no matter what these parents do, so they found their holiness, and their peace, in being the best parents they could, and letting God sort out the rest.

May God bless our families, warts and all.

Español

Mi relación con mi padre, como la relación entre todos los padres e hijos, es complicada. A mi papá le gusta cualquier cosa con un motor, y es más feliz cuando está lavando o manteniendo o arreglando su variedad de coches, camiones, barcos y motos. Él siempre me quería ayudar, por supuesto, pero me pareció muy aburrido. Prefería estar adentro, jugando con mis legos o mi conjunto de erección, o leyendo un libro. Al envejecer, me di cuenta de que nuestros intereses divergentes eran una fuente de tristeza para mi padre. Soy su primer hijo y único hijo varón, y quería compartir conmigo todas las cosas que amaba, pero no me interesaba. Y, viceversa, ha sido difícil para mi padre presbiteriano raramente-asistir para emocionarse acerca de las pasiones religiosas de su hijo el sacerdote católico.

Te lo digo porque pensar en mi propio padre me ayuda a entender a Abram en nuestra primera lectura, y por qué Abram insistió tanto en tener un heredero que era su propio hijo. Creo que fue porque Abram, como mi propio padre, como cualquier padre, quería saber que había alguien que venía tras él, que era como él.

No sé por qué este es un deseo humano tan fuerte, pero lo es. Algunos han sugerido que buscamos herederos porque buscamos la inmortalidad a través de ellos, así que cuanto más se parecen a nosotros, más inmortales nos sentimos. Personalmente, creo que es porque la semejanza engendra confianza. Cuanto más como nosotros alguien es, más confiamos en ellos. Así que, si vamos a entregar el trabajo de nuestra vida, queremos dárselo a alguien que es como nosotros, porque confiamos en que ellos lo llevarán correctamente. Confiamos en que se lo estamos dando a nuestros seres más jóvenes, y no a un extraño. Vamos a llamar a este impulso el “mini-yo complejo”.

Ahora, tan natural como el complejo mini-yo es, tanto como atraviesa épocas y culturas, el punto de esta homilía no es elogiarlo, sino atacarlo, por dos razones. La primera es porque nos distrae de lo que es verdaderamente importante, y la segunda es porque nos hace sentir inmerecidamente culpables por nuestros hijos.

Así que, a la primera: ¿Cuál es más importante, la acción o el resultado? La mayoría de nosotros hemos sido entrenados para responder “el resultado” porque si algo no tiene un efecto que dure, parece fútil y sin sentido. Pero esto es la antítesis del pensamiento católico. Nosotros, los cristianos, sabemos que Dios sólo nos responsabiliza por aquellas cosas que podemos controlar, es decir, nuestras acciones. No podemos controlar si nuestras acciones traen los resultados deseados o no, así que Dios no presta ninguna atención a los resultados. El problema, entonces, con el complejo mini-yo, con la obsesión de un heredero, es que pone nuestro enfoque y nuestra esperanza en algo que no podemos controlar y que a Dios no le importa. Amigos míos, no somos juzgados por nuestro legado. En lugar de preguntar “¿Qué pasará cuando me haya ido?” deberíamos preguntarnos “¿Estoy esforzándome por ser la mejor persona que pueda ser? ¿Estoy decidido a hacer el mejor trabajo que pueda con el tiempo y los recursos que tengo? ” Y si podemos responder “sí” a estas preguntas, si honestamente podemos decir que estamos haciendo nuestro mejor esfuerzo, entonces nada más importa, ni siquiera el futuro.

La segunda razón para abandonar el complejo mini-yo es porque he visto a demasiadas personas sentirse culpables por sus hijos. Para usar otro ejemplo de mi propia relación con mi padre: decidí ir a un colegio experimental y desconocido, que mi padre pensaba que era una idea horrible cuando también tenía cartas de Columbia y Rice y el programa de honores de la UW. Y luego, unos años más tarde, cuando finalmente había hecho las paces con esa decisión, le dije que, de todos modos, estaba desperdiciando todo para convertirme en un sacerdote católico. En ambos casos mi papá pensó que eran decisiones radicales, imprudentes, y en ambos casos sintió que podría tener o debería haber hecho más para influir en mí antes de tomar estas decisiones. Sí, tal vez el divorcio no sucedió, tal vez si hubiéramos vivido en el mismo estado, las cosas podrían haber sido diferentes. O tal vez soy terco, argumentativo, y seguro de sí mismo, y yo iba a tomar mis propias decisiones locas de todos modos. Propina profesional: era probablemente la opción número dos.

El problema con el complejo mini-yo es que nos convence de que de alguna manera hacemos o debemos tener control sobre nuestros hijos, y así si nuestros hijos no resultan exactamente como esperamos (lo que suele decirse, una versión mejorada de todo lo que nos gusta de nosotros mismos), entonces pensamos que de alguna manera hemos fallado.

¡Tenemos que detenerlo!

Todos necesitamos admitir a nosotros mismos que los niños tienen libre albedrío, igual que nosotros. No puedo decirles cuántas personas vienen a confesarse y confesar los pecados de sus hijos. Lo. Detengan. Cuando una persona mayor de siete años toma una decisión, ellos y ellos solos serán responsabilizados. Hay una razón por la que no permitimos que los padres acompañen sus hijos en el confesionario incluso a los de tercer grado. Sí, los niños ciertamente necesitan la guía de sus padres, desde la edad de siete hasta la edad de cincuenta y siete, pero la carga de la libertad descansa equitativamente en todos nosotros, y nadie, ni siquiera alguien tan influyente como un padre, puede asumir la responsabilidad de las elecciones libres del otro.

Esto, creo yo, es, en última instancia, por qué Dios le pidió a Abraham que sacrificara a Isaac, que se discute en nuestra segunda lectura de hoy. Abraham en nuestra primera lectura se centró tanto en la adquisición de un heredero de su propia línea de sangre que cayó de cabeza en el complejo mini-yo. Así que para mostrar a Abraham cuán poco control tenía en realidad sobre su futuro, Dios le pidió a Abraham que le diera a Isaac; y, para el crédito eterno de Abraham, confía en Dios y lo hace. Al hacerlo (ahora presten atención, esta es la parte importante), al hacerlo, Abraham recibió de nuevo a Isaac. En otras palabras, al renunciar al control sobre Isaac, Abraham recibe de nuevo a su hijo de una manera nueva y mejor, como un don en lugar de una herramienta de inmortalidad.

Creo firmemente que esto es lo que Dios desea para los padres, que siempre deben recibir a sus hijos como un regalo. Incluso cuando estas manzanas han caído muy, muy lejos del árbol. Incluso cuando estos niños están haciendo cosas estúpidas, causando drama familiar, o de otra manera son tercos, argumentativos y seguros de sí mismos. Incluso entonces son un regalo. Pero esto requiere renunciar al control y, en cierto punto, incluso la responsabilidad de estos niños. Porque un regalo siempre viene del exterior. Si seguimos pensando que nuestros hijos son meramente una extensión de nosotros mismos, que deben ser exactamente como sus padres, entonces nunca pueden ser un regalo, porque nunca podemos pensar en ellos como fuera de nosotros. Pero si podemos ver a los niños como individuos independientes, únicos, dados a nosotros por un tiempo de Dios, pero nunca completamente nuestros, entonces los recibiremos de nuevo como los regalos que ellos son.

Esto no quiere decir que los padres deben tener una actitud de manos fuera. ¡Lejos de eso! Los padres tienen una grave responsabilidad de formar a sus hijos con una cosmovisión cristiana y hábitos cristianos. Pero, una vez más, esta formación no puede ser juzgada por los resultados, sino sólo por cada momento en el tiempo, porque estos momentos son las únicas cosas que podemos controlar.

Esto tampoco quiere decir que cada decisión divergente sea irrelevante y sin sentido. Mi padre proporcionó un punto de vista importante y tenía razón al ser crítico con las decisiones que tenían profundos efectos en mi futuro. Muchos de nuestros hijos eligen alejarse de una relación sacramental con Jesús, y estamos en lo correcto al tratar de llamarlos de nuevo al Señor. Pero el hecho es que los niños tienen libre albedrío. La carga de la libertad descansa equitativamente en todos nosotros. Después de la edad de dieciocho años, una decisión pobre, estúpida, o imprudente es mejor dirigida con amor, misericordia y compasión, en lugar de culpa, enojo o vergüenza.

Finalmente, probablemente porque son la Sagrada Familia, María y José nos dan un ejemplo excelente en el Evangelio de hoy de no caer presa de la tentación de controlar. Si yo fuera ellos en el templo, estaría enloqueciendo. Un tipo agarra al bebé y grita “Finalmente puedo morir. ¡He visto la gloria de Israel!” Y entonces esta anciana se acerca a ellos y comienza a predicar a todo el templo acerca de lo increíble que es este bebé. Aparte de ir a esconderse bajo una roca, ¿qué debían hacer María y José sobre todo esto? Su hijo está atrayendo a un montón de locos, y no parece haber nada que puedan hacer para detenerlo.

Lo que es hermoso sobre el ejemplo de estos santos padres es que ellos no hacen nada. No intentan detener lo que está sucediendo, porque saben que no tienen absolutamente ningún control sobre la situación, y que su hijo hará muchas cosas, y le harán muchas cosas, que no entienden. Así que se centran en lo que pueden controlar. Ellos realizan obedientemente los sacrificios del templo como vinieron a hacer, y luego se van a casa y crían a su hijo lo mejor que pueden. Jesús va a ser Jesús, no importa lo que hagan estos padres, así que encontraron su santidad, y su paz, en ser los mejores padres que pudieron, y dejando que Dios solucione el resto.

Que Dios bendiga a nuestras familias, verrugas y todo eso.

Excellent Father Moore !!! This hit home. Thank You and Merry Christmas Season. Blessings in the new year… RR

Good reflection on parenting.